Born on Nov. 22, 1912 in New York City, Doris Duke was the only child of James Buchanan (J.B.) Duke, a founder of the American Tobacco Company and Duke Power, and his second wife, Nanaline Holt Inman Duke. When J.B. Duke died in 1925, he divided his fortune between Doris and the Duke Endowment—a foundation that he established to serve the people of the Carolinas and continues to operate as an independent foundation, headquartered in Charlotte. Because Doris Duke was only 12 years old when her father passed, she inherited her share of his estate over a series of years, beginning with her 21st birthday.

Upon receiving the first installment in 1934, Doris Duke established Independent Aid, Inc., her first charitable foundation. Over the course of her life, Duke gave away the equivalent of more than $400 million in today’s dollars—often anonymously. Her philanthropic interests were wide ranging and included supporting the welfare of women and children, mental health, social work, Native communities, early family planning efforts, historically Black colleges and universities, environmental conservation and AIDS research, among others.

In 1935, Duke married James “Jimmy” H.R. Cromwell in New York City, and the couple embarked on a honeymoon tour of the world, spending significant time in the Middle East and Asia. Duke amassed a sizeable collection of art throughout their travels. They concluded their trip in Honolulu. During their stay, Duke famously befriended the Kahanamokus, a prominent Native Hawaiian family, who quickly became an integral part of her social circle and introduced her to surfing and many other staples of Honolulu living.

Finding herself captivated by the cultures she experienced during her honeymoon as well as by life in Hawaii, she commissioned a home in Honolulu to be designed by Marion Sims Wyeth (1889-1982). Shortly after, the construction of what would become Shangri La began. Taking an active role in developing the plans, Duke intended the design to be influenced by the Islamic artworks she had collected during her travels and envisioned a growing collection that would be shaped in turn by the architecture. In addition to commissioning local Hawaiian designers and artisans, she also hired traditional craftsmen from India, Morocco, Syria and Iran.

Shangri La retained a permanent place in Duke’s life, and she continued to acquire and commission artworks for the seasonal home over the course of several decades. Today, Shangri La is a museum for learning about the global cultures of Islamic art and design.

During the Second World War, Duke applied for the United Seaman’s Service (USS), established to care for the needs of merchant seamen, in 1944. A few months later, she was accepted and subsequently set sail to Alexandria, Egypt to begin her work as an assistant director of the American Seaman’s Club. In 1945, with Alexandria becoming less prominent for American shipping, Duke transitioned out of the USS and joined the International News Service as a news correspondent. She was primarily stationed in Italy and, until early 1947, wrote dispatches from different parts of the country. Taking a continuing interest in journalism and writing, her work at the International News Service led her to become a staff member of Harper's Bazaar in Paris at the conclusion of the war.

After the war, Duke became more active in the maintenance of Duke Farms, the New Jersey estate conceived by her father to resemble the North Carolina Piedmont farms of his youth. With a growing interest in horticulture and natural preservation, Duke developed a close friendship with Pulitzer Prize-winning author, scientific farmer and conservationist Louis Bromfield (1896 – 1956). Duke’s horticultural pursuits left a lasting impact on Duke Farms. It was there that Duke cultivated, hybridized and propagated orchids—including the Phalaenopsis Doris, an orchid hybrid registered by Duke Farms and a common orchid variant for mass market commercial sales. Today, Duke Farms is a world class environmental center in Hillsborough, N.J.

Over the course of her life, Duke gave away the equivalent of more than $400 million in today’s dollars—often anonymously.

Throughout her life, Duke was also both a patron of and a participant in the performing arts. She actively pursued various art forms, including jazz piano and composition, which she studied at the famed “Jazz Loft” on Sixth Avenue in New York City. She also had a passion for modern dance and worked under the tutelage of celebrated choreographer Martha Graham.

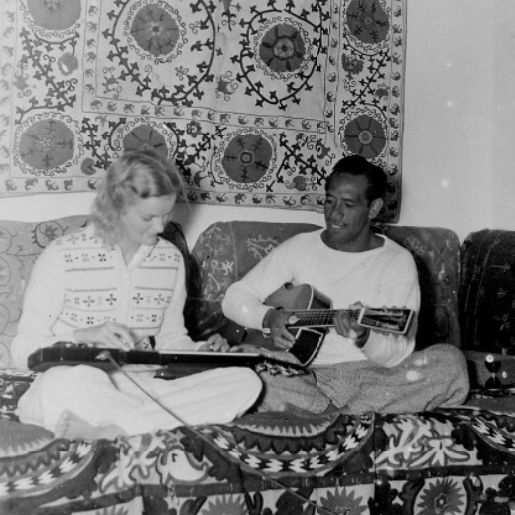

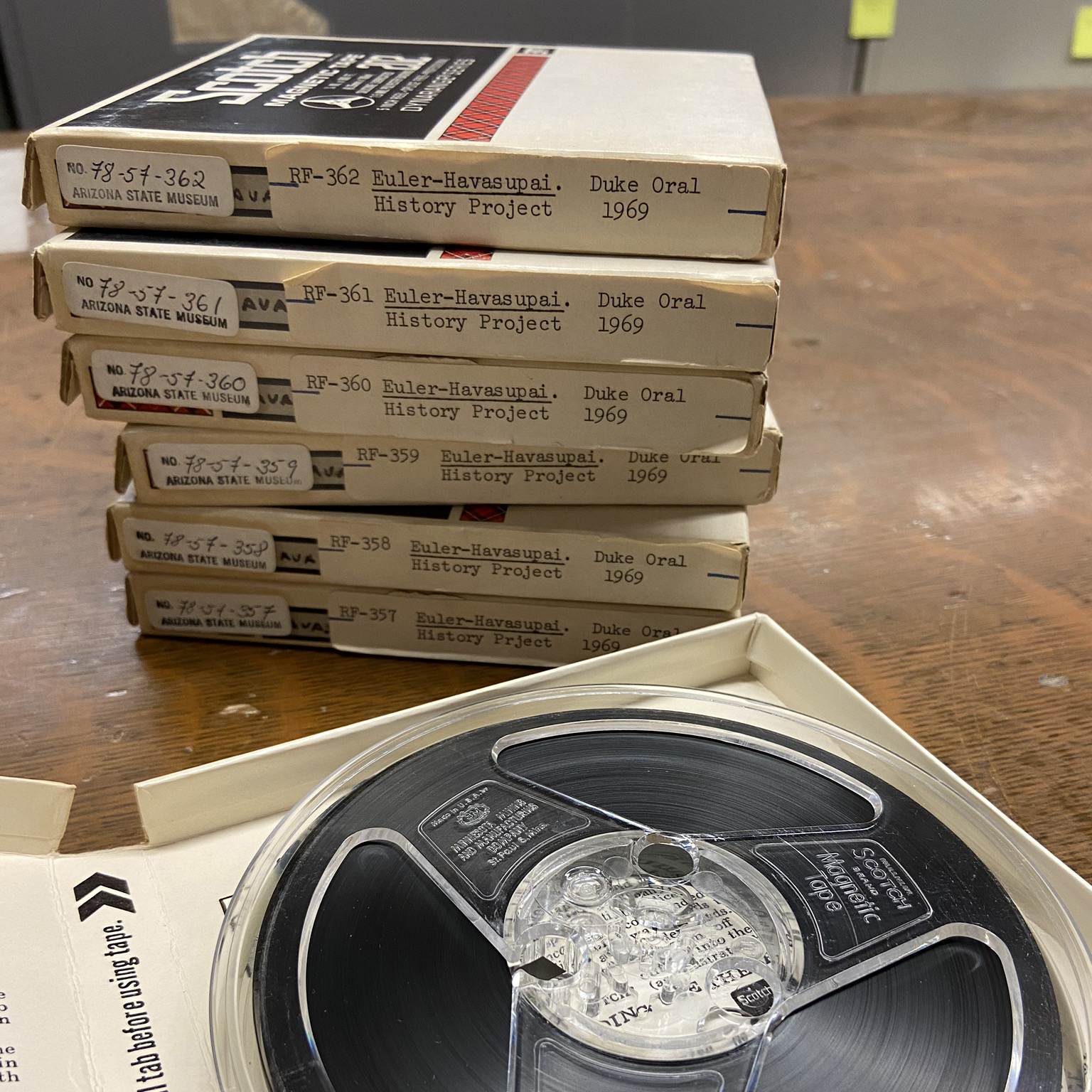

Duke’s personal philanthropy evolved with the times. In 1963, she began a sizeable effort to provide funding to historically Black colleges and universities, granting nearly $1.6 million to 15 institutions, including the North Carolina College at Durham, Shaw University in Raleigh and Bennett College in Greensboro. For nearly 20 years, Duke also contributed funds to support Native communities. One of the most widely known instances of this philanthropy was the Doris Duke American Indian Oral History Project. Beginning in 1966, the program provided grants to eight universities across the U.S. to record thousands of spoken histories from Native leaders and culture bearers around the country and to return these stories to the Tribes and communities that provided them.

In 1968, Duke also established the Newport Restoration Foundation, through which she gave more than $21.9 million over the course of 14 years to address the deterioration of Newport, R.I.’s historically significant architecture. Having restored a total of 83 properties, the Newport Restoration Foundation now operates three local museum properties that are open to the public, including Rough Point, Duke’s Newport home that is now a public museum featuring extensive collections of fine and decorative arts and educational programs.

At the age of 80, in 1993, Doris Duke died in her Beverly Hills home with an estate valued at nearly $1 billion. In her will, Duke left her fortune, properties and extensive collections of art to a foundation to be created in her name that would simultaneously operate Shangri La and Duke Farms. To that end, the Doris Duke Foundation has developed its mission, focus areas and strategies based on Duke’s written guidance as well as the personal passions and philanthropic endeavors that she pursued and supported throughout her life.