Beginning in late 2011, the Child Abuse Prevention Program (CAPP) embarked on a strategic review of its grant making over the course of the previous decade. From this self-evaluation, a new vision emerged for the program, resulting in a change to its mission and its approach. While CAPP remains committed to efforts that concentrate on prevention rather than those that address the needs of children who have already experienced maltreatment, the foundation has chosen to shift the program's focus to the broader goal of achieving child well-being through a public health approach. Below is a journey through the process that led us to that determination, an exploration of what we have learned along the way and a detailed look at how this shift in outlook will shape decisions about what the program funds.

A Look Back at CAPP's Initial Approach

When CAPP began making grants in 2001, the program's main focus was on the prevention of child abuse. Nearly all private and government funding for child abuse-related work was, and continues to be, committed to the identification and protection of children who have already been abused or neglected. In concert with its goal, CAPP chose to support programs that assist parents in forming nurturing relationships with their children, especially when the children are very young. This focus reflected the realities of child abuse and neglect. For the vast majority of children who are maltreated, a parent is the perpetrator. Here, CAPP's central prevention strategy was to educate parents and increase their parenting skills. The main way the program sought to reach parents was through "non-stigmatizing" systems that the public did not perceive as punitive. Child protection systems, which oversee child removal from families, were thus excluded as a prevention setting. CAPP supported early childcare settings as a central channel to reach parents as well as primary health care services.

Learning From More Than a Decade of Successful Funding

While the "one family at a time" casework approach of transferring knowledge and skills to parents has its merits, our review identified several challenges to this approach. First, it is very difficult to determine which parents need these services. The risk factors for child abuse and neglect are quite common—poverty, racial-ethnic minority status, domestic violence, substance use, mental illness, etc.—but, fortunately, serious child abuse is quite rare.[1] Each year about 1,500 children die from child abuse or neglect. In other words, most families that experience social and material hardships manage to take care of their children.

Next, while there are effective program approaches, a number of barriers exist to their large-scale implementation. Such programs fall broadly into two categories: 1) home visiting in support of caregivers and their infants and young children; and, 2) high quality early childcare centers. Delivering these services to intended recipients has proved a challenge, both because of program cost and program participation rates. Over the long term, excellent evidence-based approaches are cost-effective, but delivery costs are nonetheless quite high and such costs are a barrier to adoption. Also, not all those who are assessed to need and are offered an intervention program will agree to fully participate. In research studies, successful delivery of a "full dose" of the intervention is often limited to about half of those initially targeted—and in actual practice, the proportions served may be even lower.

Seeking Approaches Offering the Most Benefit to the Most People

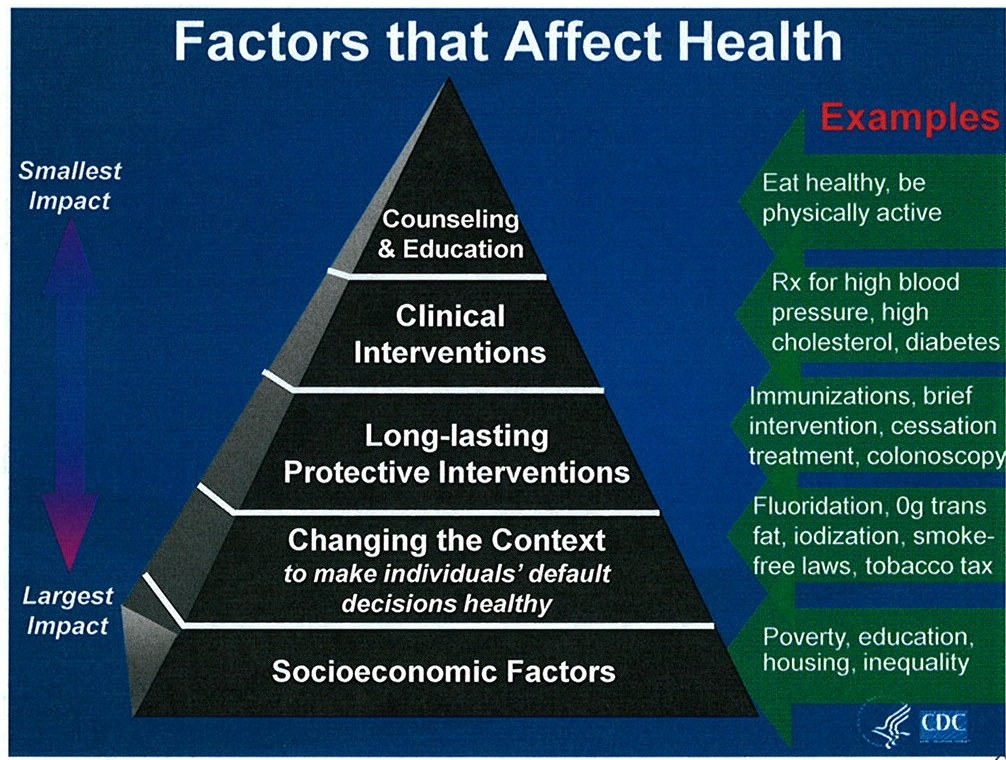

The logic behind trying to reach individual families to help them become good parents makes understandable sense, but the history of public health interventions shows that strategies using the counseling approach are high cost, require a high degree of individual effort and have relatively low impact. This is summarized pictorially in the pyramid at right, proposed by Dr. Thomas Frieden and now adopted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), of which he is the director.[2]

The logic behind trying to reach individual families to help them become good parents makes understandable sense, but the history of public health interventions shows that strategies using the counseling approach are high cost, require a high degree of individual effort and have relatively low impact. This is summarized pictorially in the pyramid at right, proposed by Dr. Thomas Frieden and now adopted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), of which he is the director.[2]

The pyramid displays how interventions that change the population's environment so that the healthy choice is also the default choice have the highest impact—in part because they require the least individual effort. These environmental strategies may also be the most cost effective. [3] Placing fluoride in the water is an iconic example of how to make a healthy option universal. Dentists may counsel individuals on dental hygiene, schools can bring dental services directly to underserved populations, and a survey can identify children with decayed teeth so that they can be targeted for additional care. But, the public health accomplishment in dental care that has delivered the most good to the most people is fluoridation. In fact, the CDC noted fluoridation as one of the top ten public health accomplishments of the 20th century.[4] [5]

CAPP has so far focused its efforts mainly on developing useful programs that target the top of the pyramid: counseling interventions that are delivered to one person (or family) at a time. In reframing the strategy, we have proposed to "move down" the pyramid to test whether strategies analogous to "fluoride in water" can be found for the prevention of child abuse and neglect.

How Advances in the Field Have Influenced CAPP's New Vision

In addition to this reframing, our review found that recent knowledge is changing how the field views abuse and neglect, mainly through the science of early brain development. Epidemiological studies have shown that experiencing adverse circumstances in early life has a lasting and broad impact on adult outcomes. In recent years, researchers have found that exposure to stress in early life results in enduring effects on brain architecture that may help explain unfavorable behavioral patterns that are displayed by children who experience abuse and neglect. In early 2012, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued both a policy statement and a technical report on "The Lifelong Effects of Early Childhood Adversity and Toxic Stress." [6]

The implication of these findings is that abuse and neglect as identified and reported to child protection authorities represents the "tip of the iceberg" of harms that occur to children when they are unable to establish loving, stable relationships with a caregiver. As a consequence, attention should focus instead on the assurance of child well-being, not simply prevention of abuse. This shift in focus greatly broadens the charge to protect children, and such a perspective is gaining ground. Bryan Samuels, Federal Commissioner of the Administration on Children Youth and Families, in April 2012 issued a federal Information Memorandum that stressed child well-being as the most pressing future challenge for his agency and the field.[7]

A Revised Mission and Refocused Strategic Priorities

Since 2009, the approved wording of the CAPP mission has been "to protect children from abuse and neglect in order to promote their healthy development." Based on CAPP's new emphasis on child well-being, the foundation has modified its mission as follows: "to promote children's healthy development and protect them from abuse and neglect."

Going forward, the three components of CAPP's 2008 strategy [8] will be retained; however, the application of those strategic priorities will shift from interventions focused at the level of the individual (or family) to a broader public health based approach:

Build the repertoire of prevention strategies. First, in a shift from our previous focus on parent education, this strategy now examines place-based approaches. These are interventions that seek to ensure that a community, not only a parent, provides a setting that promotes child well-being. Ample data show that, in addition to parent characteristics, the occurrence of child abuse and neglect tracks with neighborhood characteristics indicating social distress. Conversely, positive community characteristics can help protect early childhood. Evidence is emerging that "collective efficacy," or the mutual trust among neighbors and the willingness to act for the common good, can change individual risk levels.

Expand capacity of existing systems. Second, this strategy will use existing systems that offer a channel to entire populations characterized by high risk for child abuse and neglect as opposed to targeting families based on individual characteristics. By working within existing systems that already serve populations where risk is especially high, more intensive—often higher—cost interventions can be targeted more effectively and efficiently.

Develop and Disseminate Knowledge. Last, there remains a need to build a broader audience for information that helps prevent child abuse and neglect. The recently renamed Doris Duke Fellowships for the Promotion of Child Well-being,[9] which supports doctoral students engaged in this multidisciplinary area, are an important contribution to building research and practice capacity in the field. Other approaches might include the use of popular media outlets.

Through these three reshaped strategies, CAPP now seeks a public health approach that may draw on many disciplines. In some ways, this effort will revisit work that began 100 years ago at the beginning of the 20th century, when social reformers began to think creatively about childhood. Recognizing that urbanization and industrialization had changed the modern world forever, artists, architects, the settlement house movement, educators and others all came together to consider how to promote and protect childhood and, in the words of Jane Addams, "preserve its wonder." As we embark on executing this exciting new vision for the program, we look forward to sharing more of what we learn along the way.

[1] Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children's Bureau. (2011). Child Maltreatment 2010. Available from: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/stats_research/index.htm#can.

[2] Frieden, TR. A Framework for Public Health Action: The Health Impact Pyramid. American Journal of Public Health 2010:100(4):590-595.

[3] Chokshi DA, Farley TA. The Cost-Effectiveness of Environmental Approaches to Disease Prevention N Engl J Med 2012; 367:295-297.

[4] "Ten Great Public Health Achievements – United States, 1900-1999." MMWR 1999;48(12):241-243. Available for access at: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00056796.htm

[6] Garner AS, et al. Early Childhood Adversity, Toxic Stress, and the Role of the Pediatrician: Translating Developmental Science into Lifelong Health. Pediatrics 2012:129:e224-e231

[7] Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (ACYF). (2012). Information Memorandum: Promoting Social and Emotional Well-being for Children and Youth Receiving Child Welfare Services. (ACYF-CB-IM-12-04). Washington, DC. Access at: www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/im1204.pdf

[8] The strategy was approved by the Board in early 2009 following a 2008 review of the program.

[9] Formerly known as The Doris Duke Fellowships for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect.